Abstract

The molecular mechanisms governing orderly shutdown and retraction of CD4+ type 1 helper T (TH1) cell responses remain poorly understood. Here we show that complement triggers contraction of TH1 responses by inducing intrinsic expression of the vitamin D (VitD) receptor and the VitD-activating enzyme CYP27B1, permitting T cells to both activate and respond to VitD. VitD then initiated the transition from pro-inflammatory interferon-γ+ TH1 cells to suppressive interleukin-10+ cells. This process was primed by dynamic changes in the epigenetic landscape of CD4+ T cells, generating super-enhancers and recruiting several transcription factors, notably c-JUN, STAT3 and BACH2, which together with VitD receptor shaped the transcriptional response to VitD. Accordingly, VitD did not induce interleukin-10 expression in cells with dysfunctional BACH2 or STAT3. Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid CD4+ T cells of patients with COVID-19 were TH1-skewed and showed de-repression of genes downregulated by VitD, from either lack of substrate (VitD deficiency) and/or abnormal regulation of this system.

Main

A substantial number of patients with COVID-19 develop severe and life-threatening hyper-inflammation and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). Mortality from severe COVID-19 remains high, in part due to the limited range of specific immunomodulatory therapies available. Survivors, and those with milder disease, may lose significant tissue function from persistent inflammation and fibrosis, causing chronic lung disease. The efficacy of dexamethasone in reducing mortality indicates the importance of inflammation to disease severity1. Improved understanding of the basic mechanisms of COVID-19 will aid rational drug design to reduce morbidity and mortality.

Pro-inflammatory immune responses are necessary for pathogen clearance but cause severe tissue damage if not shut down in a timely manner2. The complement system is instrumental in pathogen clearance via recruitment and activation of immune cells3. In brief, complement (C)3, a pro-enzyme, is activated in response to pathogen- or danger-sensing (the lectin pathway), immune complexes (classical pathway) or altered self (alternative pathway) to generate active C3a and C3b fragments, which recruit and activate immune cells and instigate activation of downstream complement components4. Complement activation is a pathophysiological feature of ARDS of many etiologies5 and mediates acute lung injury driven by respiratory viruses6. Circulating concentrations of activated complement fragments are high in COVID-19, correlate with severity and are independently associated with mortality7,8. Polymorphisms in complement regulators are, likewise, risk factors for poor outcomes9. Animal models of other beta-coronaviruses have indicated complement as part of a pathologic signature of lung injury that can be ameliorated by complement inhibition10. Emerging clinical trial evidence, from small numbers of treated patients, also points to potential benefits of complement targeting in COVID-19 (ref. 11).

The complement system is both hepatocyte-derived and serum-effective, but also expressed and biologically active within cells. Notably, activated CD4+ T cells process C3 intracellularly to C3a and C3b via cathepsin L (CTSL)-mediated cleavage12. We have recently shown that SARS-CoV2-infected respiratory epithelial cells express and process C3 intracellularly via a cell-intrinsic enzymatic system to C3a and C3b13. This represents a source of local complement within SARS-CoV2-infected lungs, where plasma-derived complement is likely to be absent, and signifies the lung epithelial lining as a complement-rich microenvironment. Excessive complement and IFN-γ-associated responses are both known drivers of tissue injury and immunopathogenesis14,15. On CD4+ T cells, C3b binds CD46, its canonical receptor, to sequentially drive TH1 differentiation followed by their shut down, represented by initial production of interferon (IFN)-γ alone, then IFN-γ together with interleukin (IL)-10, followed by IL-10 alone16. Expression of IL-10 by TH1 cells is a critical regulator of TH1-associated inflammation2. However, the exact molecular mechanisms governing orderly regulation of TH1 responses culminating in IL-10 expression remain poorly understood and may be critical in the recovery phase of COVID-19 and other TH1-mediated inflammatory diseases.

VitD is a fat-soluble pro-hormone carefully regulated by enzymatic activation and inactivation. Most VitD is synthesized in the skin on exposure to ultraviolet B (UVB) radiation from sunlight, then undergoes sequential hydroxylation to 25(OH)VitD and 1,25(OH)2VitD, classically in the liver and kidneys, respectively. VitD has immunomodulatory functions, hence, VitD deficiency is associated with adverse outcomes in both infectious17 and autoimmune diseases18. There are compelling epidemiological associations between incidence and severity of COVID-19 and VitD deficiency/insufficiency19, but the molecular mechanisms remains unknown.

We found TH1-skewed CD4+ T cell responses in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) of patients with COVID-19. As this is a complement-rich microenvironment, we investigated the molecular mechanisms governing orderly shutdown of TH1 responses induced by CD46 engagement. We found that CD46 induces a cell-intrinsic VitD signaling system, enabling T cells to both fully activate and respond to VitD. This process was primed by epigenetic remodeling and recruitment of four key transcription factors (TFs), VitD receptor (VDR), c-JUN, STAT3 and BACH2. Last, we examined these pathways in CD4+ T cells from the BALF of patients infected with SARS-CoV2 and found it to be impaired.

Results

COVID-19 CD4+ cells show TH1 and complement signatures

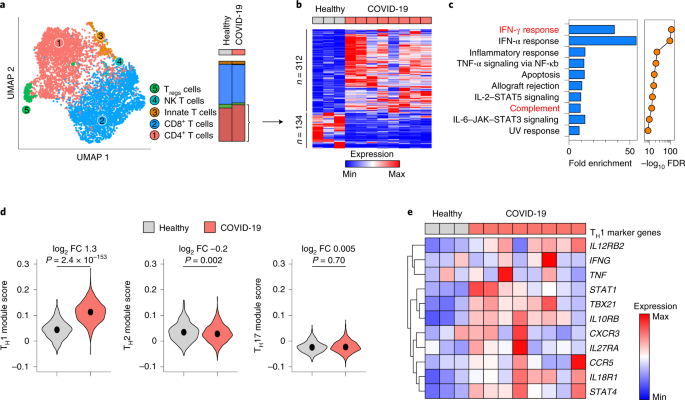

We analyzed single-cell RNA-sequencing (scRNA-seq) data from the BALF and peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) of patients with COVID-19 and healthy controls (GSE145926, GSE122960 and GSE150728). Because immunity to both SARS-CoV1 and MERS-CoV is mediated by, among other cells, IFN-γ-producing CD4+ memory T cells20 and development of TH1-polarized responses in SARS-CoV2 infection21 is suspected to contribute to pathogenic hyper-inflammation, we focused our analyses on CD4+ T cells. T cell populations within BALF (Extended Data Fig. 1a,b) comprised five major sub-clusters, including CD4+ helper T cells, according to well-characterized markers (Fig. 1a and Extended Data Fig. 1c). Although the proportion of T cells that were CD4+ did not differ between patients and controls (Fig. 1a and Extended Data Fig. 1d), 312 genes were upregulated and 134 genes were downregulated in patients' CD4+ T cells (Fig. 1b and Supplementary Table 1a). These differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were enriched in noteworthy biological pathways, including IFN-γ response and complement (Fig. 1c and Supplementary Table 1b). Examination of transcriptional programs by module score indicated that CD4+ T cells in patients were preferentially polarized toward TH1, as opposed to type 2 helper T (TH2) cells or the TH17 subset of helper T cell lineages (Fig. 1d). Consistently, expression of core TH1 marker genes were higher in patients (Fig. 1e).

a, Uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP) of scRNA-seq showing sub-clustering of T cells from BALF of n = 8 patients with COVID-19 and n = 3 healthy controls. Stack bars (right) show cumulative cellularities across samples in patients and controls. Dot plot of marker genes for these clusters are shown in Extended Data Fig. 1c. NK, natural killer. b,c, Heat map showing DEGs (at least 1.5-fold change in either direction at Bonferroni adjusted P < 0.05 using two-sided Wilcoxon rank-sum test) between helper T cells of n = 8 patients with COVID-19 and n = 3 healthy controls (b) and enrichment of those DEGs in Hallmark MSigDB gene sets (c). NF, nuclear factor; TNF, tumor necrosis factor. False discovery rate (FDR)-corrected P values in c are from hypergeometric tests. Highlighted in red in c are Hallmark IFN-γ response and complement pathways. d, Violin plots showing expressions of TH1-, TH2- and TH17-specific genes, respectively, summarized as module scores, in BALF helper T cells of patients with COVID-19 and healthy controls. Medians are indicated. Exact P values have been calculated using two-tailed Wilcoxon tests. FC, fold change. e, Heat map showing mean expression of classic TH1 marker genes in BALF helper T cells of patients with COVID-19 and healthy controls. Data are sourced from GSE145926 and GSE122960.

Source data

Full size image

Enrichment of complement pathway (Fig. 1c) was notable because (1) we recently identified complement as one of the most highly induced pathways in lung CD4+ T cells22; (2) SARS-CoV2 potently induces complement, especially complement factor 3 (C3), from respiratory epithelial cells13; (3) COVID-19 lungs are a complement-rich microenvironment23; and (4) CD4+ T lymphocytes in COVID-19 lungs have a CD46-activated signature13. Because CD46 drives both TH1 differentiation and shutdown, characterized by IFN-γ and IL-10 expression, respectively16, we determined the state of TH1 cells in COVID-19 BALF. IL10 mRNA was dropped out in scRNA-seq, but detectable in bulk RNA-seq from BALF (Extended Data Fig. 1e). Consistently we observed significant enrichment of TH1-related genes in patient cells compared to controls, but ~fivefold lower IL10 (Extended Data Fig. 1e). Similar examination within scRNA-seq of PBMCs (Extended Data Fig. 2a,b) did not show meaningful differences in TH1, TH2 or TH17 lineage genes (Extended Data Fig. 2c). Collectively, these data indicated the TH1 program and complement signature as features of helper T cells at the site of pulmonary inflammation where virus-specific T cells may be concentrated24 and are consistent the notion that COVID-19 TH1 cells were in the inflammatory phase of their lifecycle compared to healthy controls.

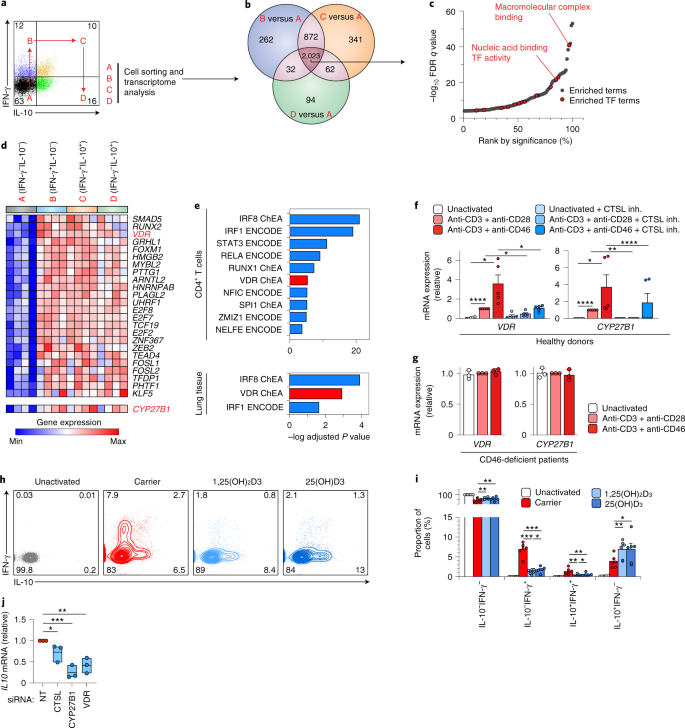

Complement induces an autocrine T cell VitD shutdown program

Prolonged and/or hyper-TH1 activity is pathogenic14,15. To discover how shutdown of TH1 cells could be accelerated, we explored how complement regulates TH1 shutdown in healthy cells. CD46, engaged by environmental or intracellularly generated C3b, works co-operatively with T cell receptor signaling to drive TH1 differentiation then subsequent shutdown16. Thus, T cells activated with anti-CD3 and anti-CD46 produce IFN-γ, then co-produce IL-10 before shutting down IFN-γ to produce only IL-10 (ref. 16) (Fig. 2a). T cells secreting neither cytokine (IFN-γ–IL-10– cells) are also appropriately activated as they upregulate activation markers (CD25 and CD69; Extended Data Fig. 3a,b) and proliferate (Extended Data Fig. 3c,d). Because this CD46 system is not present in mouse T cells, we explored its function in human CD4+ T lymphocytes. Unless specified otherwise, we used regulatory T (Treg) cell helper T cell-depleted CD4+ helper T cells (CD4+CD25–) throughout. After anti-CD3 + anti-CD46 activation, we flow-sorted cells from each quadrant by surface cytokine capture (Fig. 2a) and performed transcriptome analysis (Extended Data Fig. 4a–c). Comparing transcriptomes of IFN-γ+IL-10–, IFN-γ+IL-10+ and IFN-γ–IL-10+ against IFN-γ–IL-10– helper T cells, ~2,000 DEGs were in common (Fig. 2b, Extended Data Fig. 4d and Supplementary Table 1c,d). These were enriched for proteins whose molecular function pertained to TF biology (Extended Data Figs. 2c and 4e,f and Supplementary Table 1e), indicating that a key role of CD46 is to regulate TFs. In total, 24 TFs were induced by CD46 in cytokine producing CD4+ cells (Fig. 2d), including VDR (Fig. 2d). VDR was notable for two reasons. First, independent prediction of TFs regulating DEGs of BALF CD4+ T cells and lung biopsies of COVID-19 versus healthy donors returned VDR among the top candidates (Fig. 2e and Supplementary Table 1f). Second, CYP27B1 was concurrently induced in the transcriptome data (Fig. 2d). CYP27B1 is the 1α-hydroxylase catalyzing the final activation of VitD, converting 25(OH)VitD to biologically active 1,25(OH)2VitD. Inducible expression of CYP27B1 and VDR in helper T cells indicated the likely presence of an autocrine/paracrine loop, whereby T cells can both activate and respond to VitD. Although both are described in activated T cells25,26, the molecular mechanism and consequences are unknown. Anti-CD3 + anti-CD28 stimulation of T cells activates C3 processing intracellularly by CTSL, generating autocrine C3b to ligate CD46 on the cell surface12, which in turn enhances C3 processing to further generate C3b12. To establish that CYP27B1 and VDR are induced by complement, we confirmed that anti-CD3 + anti-CD28 and anti-CD3 + anti-CD46 both stimulate these genes in T cells and that this effect was nullified by a cell-permeable CTSL inhibitor, which blocks intracellularly generated C3b (Fig. 2f). Similarly, T cells from CD46-deficient patients did not upregulate CYP27B1 or VDR with either stimulus (Fig. 2g). Collectively, these data indicated that CD46 ligation by complement induces both the enzyme and receptor to enable helper T cells to fully activate and respond to VitD.

a, Representative flow cytometry showing IFN-γ and IL-10 in CD4+ helper T cells activated with anti-CD3 + anti-CD46 and the four quadrants (A, B, C and D) from which cells were flow-sorted for transcriptome analysis. Live and single cells are pre-gated. b, Venn diagram showing number of DEGs (± ≥1.5-fold at unadjusted P < 0.05 using analysis of variance (ANOVA)) comparing cells in quadrants B, C and D against A, respectively (n = 4 experiments). c, Enrichment of Gene Ontology molecular function terms in shared DEGs (intersect of Venn diagram in b), ranked by statistical significance. Marked are terms corresponding to TF activity. d, Heat map of induced TFs in anti-CD3 + anti-CD46-activated helper T cells at each stage of the lifecycle shown in a. Highlighted are VDR and expression of CYP27B1. e, EnrichR-predicted ENCODE and ChIP enrichment analysis TFs regulating the DEGs between COVID-19 versus healthy donor helper T cells (top) and lung biopsies (bottom). Shown are Benjamini–Hochberg adjusted P values from hypergeometric tests. f, VDR (left) and CYP27B1 (right) mRNA, in helper T cells activated or not, as indicated, with or without cathepsin L inhibitor (CTSL inh.) (n = 5 experiments). g, VDR (left) and CYP27B1 (right) mRNA in helper T cells of a patient with CD46-deficiency, activated or not, as indicated (n = 3 experiments). h,i, Representative flow cytometry (h) and cumulative data from n = 6 independent experiments (i) showing IFN-γ and IL-10 in helper T cells activated with anti-CD3 + anti-CD46 with or without carrier, active (1,25(OH)2D3) or inactive (25(OH)D3) VitD. j, IL10 in helper T cells activated with anti-CD3 + anti-CD46 with or without inactive (25(OH)D3) VitD, with siRNA targeting VDR, CTSL or CYP27B1 or non-targeting (NT) siRNA (n = 5 experiments). Data in a–d are from GSE119416. Data in e (top) are from GSE145926 and GSE122960. Data in e (bottom) are from GSE147507. Data in g are from microarrays54. Bars in f,g,i show mean + s.e.m. Box plots in j show median value and the range extends from minimum to maximum. All statistical tests are two-sided. *P < 0.05 **P < 0.01 ***P < 0.001 ****P < 0.0001 by ANOVA.

Source data

Full size image

As proof of principle that this autocrine/paracrine intracellular VitD system is involved in TH1 shutdown, we stimulated CD4+ T cells with anti-CD3 + anti-CD46 with or without active (1,25(OH)2) or inactive (25(OH)) VitD. Both forms of VitD significantly repressed IFN-γ and increased IL-10 (Fig. 2h,i), indicating that the cells had acquired the ability to activate and respond to VitD. We cultured similarly stimulated cells with inactive VitD and silenced CTSL, VDR or CYP27B1 using siRNA and assessed IL10 transcription. A significant reduction in IL10 was evident on silencing any of these components (Fig. 2j and Extended Data Fig. 5), indicating that they are all required for producing IL-10. Altogether, these data indicated existence of a complement-induced intracellular autocrine/paracrine VitD system promoting T cell shutdown.

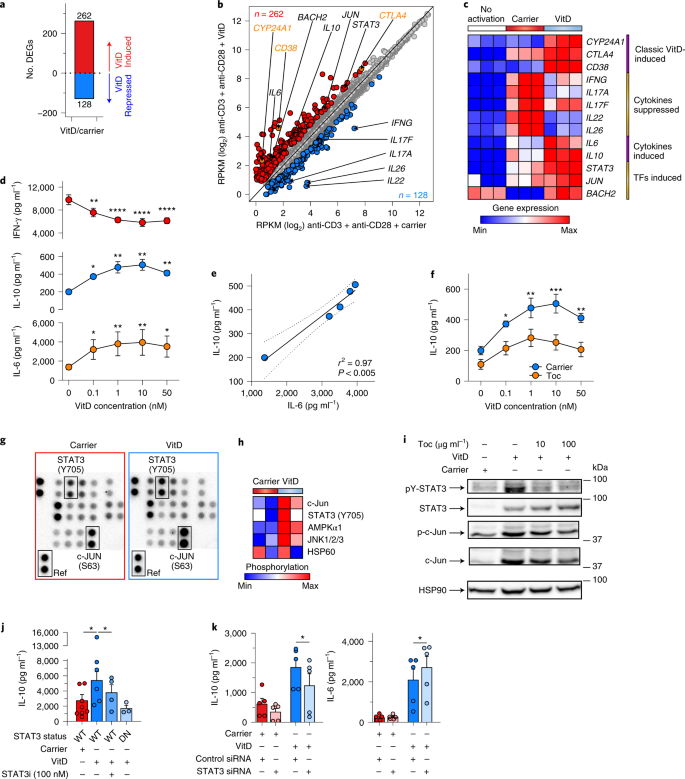

VitD induces IL-10 via autocrine/paracrine IL-6/STAT3

We next investigated the effects of VitD on CD4+ T cells. In all subsequent experiments cells were activated with anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 (as this stimulus also signals through CD46 (ref. 12)) and we used active 1,25(OH)2VitD. We confirmed that VDR protein was induced by T cell activation (Extended Data Fig. 6a), VitD-enhanced VDR expression27 (Extended Data Fig. 6a) and VitD-bound VDR translocated to the nucleus (Extended Data Fig. 6b,c). VitD upregulated 262 genes and downregulated 128 genes in helper T cells (Fig. 3a and Supplementary Table 2a,b), which was not due to alterations in cell proliferation or death (Extended Data Fig. 6d). Classical VitD-regulated genes, including CTLA4, CD38 and CYP24A1, were induced and both type 1 (IFNG) and type 17 (IL17A, IL17F, IL22 and IL26) cytokines were repressed (Fig. 3b,c), consistent with previous reports28. Genes induced by VitD included two cytokines, IL10 and IL6 and several TFs, including JUN, BACH2 and STAT3 (Fig. 3b,c). As IL-10-producing CD4+FoxP3– Treg type 1 (Tr1) cells can be induced from naive helper T cells by VitD29, we noted that genes induced/repressed by VitD were not enriched in Tr1 cell signature genes (Extended Data Fig. 6e) and did not exhibit the archetypal surface phenotype of Tr1 cells (CD49b+LAG3+ 30) (Extended Data Fig. 6f). Similarly, FOXP3, the master TF of natural Treg cells, was not upregulated by VitD (Supplementary Table 2b). Genes regulated by VitD were most significantly enriched for cytokines (Extended Data Fig. 6g). Unexpectedly, IL6, usually a pro-inflammatory cytokine, was the most highly induced gene in the hierarchy of cytokines regulated by VitD (Extended Data Fig. 7a). We confirmed repression of IFN-γ and IL-17 and induction of IL-10 and IL-6 proteins in VitD-treated helper T cells (Extended Data Fig. 7b) and noted a strong dose–response relationship between VitD concentrations and these effects (Fig. 3d). To confirm again the autocrine/paracrine VitD activation system at the protein level (Extended Data Fig. 5c), we observed repression of IFN-γ and IL-17 and induction of IL-10 and IL-6 by helper T cells treated with only inactive 25(OH)VitD, indicating intracellular conversion of 25(OH)VitD to active 1,25(OH)2VitD (Extended Data Fig. 7d).

a, Number of DEGs between VitD and carrier-treated helper T cells (± ≥1.5-fold change at FDR < 0.05). b, Scatter-plot showing mRNA expression (RPKM) of genes in helper T cells treated with VitD or carrier. VitD-induced and -repressed genes are depicted in red and blue, respectively. Noteworthy genes are annotated (black), including classical VitD-induced genes (orange); n = 3 independent biological experiments. c, Heat map showing expression of select genes from b. d, Dose–response of indicated cytokines from helper T cells treated for 72 h with VitD. Stars indicate statistically significant changes in comparison to 0 nM of VitD; n = 3 experiments. e, Pearson correlation between IL-6 and IL-10 concentrations in culture supernatants of VitD-treated helper T cells. Shown is the correlation line, plus 95% confidence interval. f, IL-10 concentrations in supernatants of helper T cells cultured with VitD, with and without tocilizumab; n = 3 experiments. g, Representative image from n = 2 experiments of a phospho-kinase array (array of 43 kinases in duplicate spots) carried out on 3-d lysates of carrier- or VitD-treated s. Location of STAT3 phosphorylated at lysine 705, c-JUN phosphorylated at serine 63 and reference spot (to which all spots are normalized) are indicated. h, Heat map showing normalized phosphorylation values of differentially phosphorylated proteins following VitD treatment (Extended Data Fig. 7i) in n = 2 donors. i, Immunoblots of lysates of helper T cells treated with carrier or VitD with and without, tocilizumab (Toc) at the concentrations shown. Shown are representative images from n = 3 experiments (quantified in Extended Data Fig. 7j). j, IL-10 production from helper T cells cultured with carrier or VitD, with or without a STAT3 inhibitor (STAT3i). Genotype of cells (WT, STAT3 wild type; DN, STAT3 dominant negative) is indicated; n = 3 experiments. Each dot represents an individual donor. k, IL-10 production from helper T cells transfected with control siRNA or siRNA targeting STAT3; n = 5 experiments. Unless indicated, all cells were activated with anti-CD3 + anti-CD28. Cumulative data in d,f,j,k depict mean + s.e.m. All statistical tests are two-sided. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001 by one-way (d,j,k) and two-way ANOVA (f).

Source data

Full size image

IL-6 is a pleiotropic cytokine expressed by most stromal and immune cells31. Yet it is not commonly attributed to CD4+ T cells. We established that IL6 mRNA and protein were produced by T cells and induced by VitD (Extended Data Fig. 7e) and that VitD treatment significantly increased intracellular expression of IL-6 (Extended Data Fig. 7f). In these experiments, there was a strong correlation between IL-6 and IL-10 produced in response to VitD (Fig. 3e), suggesting a potential causal relationship. Accordingly, we stimulated helper T cells with VitD, with or without tocilizumab, an IL-6 receptor (IL-6R)-blocking antibody used clinically to treat IL-6-dependent cytokine release syndrome, including that seen in COVID-19 (ref. 32). Tocilizumab significantly impaired IL-10 produced by VitD, indicating that IL-6R signaling induced by autocrine/paracrine IL-6 promotes IL-10 in VitD-treated helper T cells (Fig. 3f). IL-6 can cooperate with IL-27 (ref. 33) or IL-21 (ref. 34) to promote IL-10 production in mouse T cells. However, both these cytokines were repressed by VitD in our transcriptomic analyses (Supplementary Table 2b), so it did not seem likely that these cytokines cooperate with IL-6 to induce IL-10 in this setting. Addition of exogenous IL-6 without VitD did not induce IL-10 (Extended Data Fig. 7g) but increased pro-inflammatory IL-17 (Extended Data Fig. 7h), as has been reported35. These data indicate that pro-inflammatory functions of IL-6 may be restricted or averted by the production of anti-inflammatory IL-10 in the presence of VitD in human helper T cells (Fig. 3f).

Genes differentially expressed by VitD were enriched in cytokine signaling pathways, which are commonly mediated through phosphorylation of signal-dependent TFs, including JAK–STATs (Extended Data Fig. 6g). We therefore carried out a phospho-kinase protein array using lysates of carrier and VitD-treated cells. Five proteins showed significant differences in phosphorylation between carrier and VitD, most notably c-JUN and STAT3, both of which were significantly more phosphorylated (Fig. 3g,h and Extended Data Fig. 7i). Immunoblotting confirmed induction of both STAT3 protein and STAT3 phosphorylation by VitD (Fig. 3i and Extended Data Fig. 7j). IL-6 potently drives STAT3 activation by phosphorylation31. STAT3 phosphorylation induced by VitD was abrogated by blockade of the IL-6R with tocilizumab, indicating that VitD-induced IL-6 is responsible for STAT3 phosphorylation (Fig. 3i and Extended Data Fig. 7j). Conversely, STAT3 protein expression was dependent on VitD but independent of IL-6 signaling, as IL-6R blockade did not reverse its induction by VitD (Fig. 3i and Extended Data Fig. 7j). By contrast, both c-JUN expression and phosphorylation were dependent on VitD and mostly independent of IL-6 (Fig. 3i and Extended Data Fig. 7j). As VitD-induced STAT3 phosphorylation was mediated by IL-6, we investigated whether STAT3 drives IL-10 produced by VitD. Both a cell-permeable STAT3 inhibitor and knockdown of STAT3 by siRNA significantly impaired IL-10 produced in response to VitD (Fig. 3j,k and Extended Data Fig. 7k,l). Likewise, VitD failed to produce significant IL-10 from helper T cells of patients with hyper-IgE syndrome, which have dominant negative STAT3 mutations and are unable to transduce STAT3 signaling normally (Fig. 3j). Collectively, these data established that VitD induces STAT3 and IL-6 and autocrine/paracrine IL-6R engagement phosphorylates STAT3, which promotes production of IL-10.

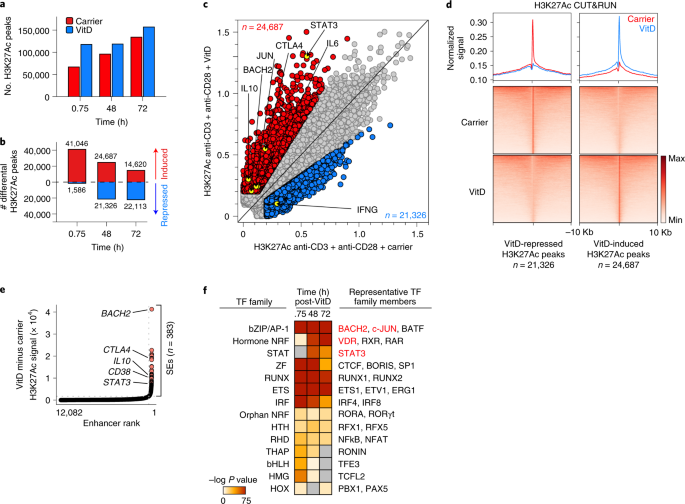

VitD alters epigenetics and recruits c-JUN, STAT3 and BACH2

VitD-bound VDR interacts with histone acetyl transferases, transcriptional co-activators, co-repressors and chromatin remodeling complexes to modulate transcription. We explored the effects of VitD on T cell epigenetic landscapes, using memory CD4+ T cells (these cells express VDR without requiring pre-activation). We profiled genome-wide histone 3 lysine 27 acetylation (H3K27Ac), a marker of active regions of the genome, using cleavage under target and release using nuclease (CUT&RUN) in VitD and carrier-treated cells. VitD induced dynamic changes in histone acetylation genome-wide (Fig. 4a,b), indicating significant changes in enhancer architecture. By 48 h after VitD treatment, ~25,000 and ~21,000 H3K27Ac peaks were induced and repressed, respectively (Fig. 4c,d and Supplementary Table 3a). Loci of genes transcriptionally induced by VitD showed increased histone acetylation and those repressed by VitD had reduced histone acetylation (Fig. 4c). The size of these peaks was significantly affected by VitD, leading to generation of new super-enhancer (SE) architectures and promotion of existing SEs (Fig. 4e). SEs are complex regulatory domains consisting of collections of enhancers critical for regulating genes of particular importance to cell identity and risk of genetic disease36,37. VitD-modified SEs included those associated with BACH2, STAT3, IL10 and other genes induced by VitD (Fig. 4e and Supplementary Table 3b). To identify potential TFs recruited to these loci, we carried out TF DNA motif finding at H3K27Ac peak loci induced by VitD. The top enriched motifs were VDR, AP-1 family members, notably c-JUN and BACH2, and STAT3 (Fig. 4f). All three of these were TFs transcriptionally induced by VitD (Fig. 3b,c) and two of these, c-JUN and STAT3, were also post-transcriptionally more phosphorylated after VitD (Fig. 3g,h). Thus, we reasoned that they are likely to play an important role in gene regulation by VitD.

a, Genome-wide H3K27Ac CUT&RUN peaks 45 min, 48 h and 72 h after VitD or carrier-treatment of helper T cells. b, Differential H3K27Ac peaks (signal ≥ 0.2, ≥1.5 × FC) after VitD or carrier-treatment of helper T cells at the indicated time points. c, Scatter-plot showing H3K27Ac CUT&RUN peak signal intensities 48 h after VitD or carrier-treatment of helper T cells. Indicated are VitD-induced peaks (red) and VitD-repressed peaks (blue). Highlighted are select peaks at loci of interest. Data show a representative example from n = 2 independent experiments. d, Heat maps showing H3K27Ac signal at VitD-repressed and VitD-induced peaks (bottom) and histograms showing normalized signals in carrier and VitD-treated cells (48 h) (top). e, Ranked order of H3K27Ac-loaded enhancers induced by VitD in helper T cells after 48 h. SEs are indicated. Marked are the relative positions, ranked according to signal intensity (higher indicates greater signal intensity), of enhancers attributed to selected genes. f, Enriched TF DNA motifs at H3K27Ac peak loci induced by VitD. Shown are TF families on the left and representative TF members enriched in the data on the right. Unless indicated, all in vitro T cell experiments depicted in Fig. 4 have been activated with anti-CD3 + anti-CD28.

Source data

Full size image

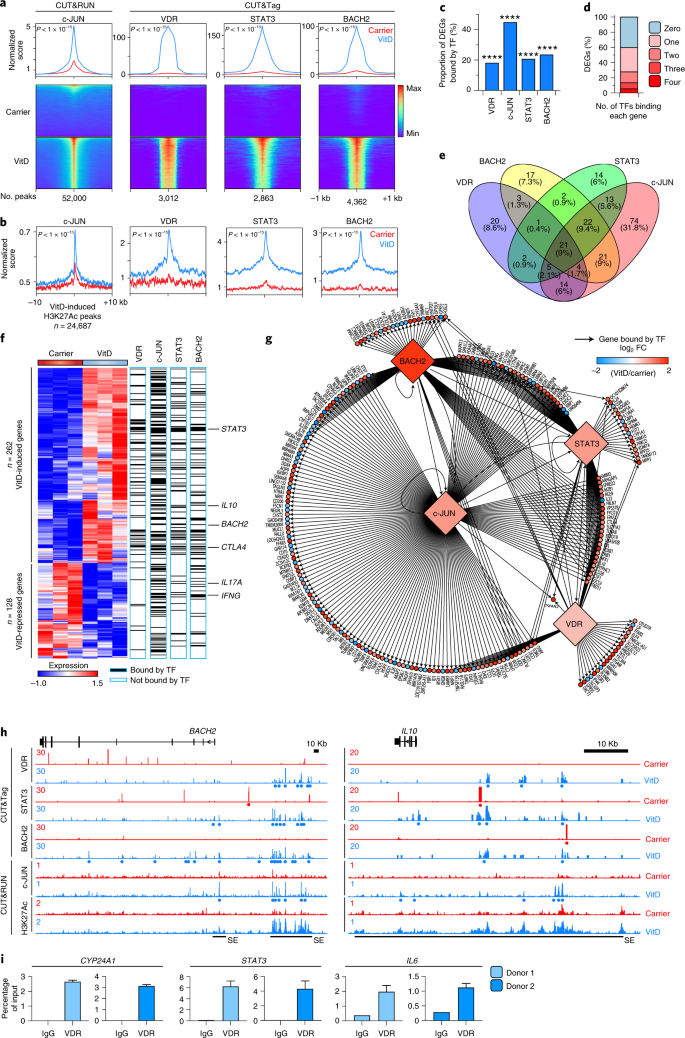

We carried out c-JUN CUT&RUN and VDR, STAT3 and BACH2 cleavage under target and tagmentation (CUT&Tag) in VitD- or carrier-treated cells (Extended Data Fig. 8a and Supplementary Table 4) to identify genome-wide distribution of these TFs. Genome-wide binding of all four TFs was increased after VitD (Fig. 5a) and they were recruited to H3K27Ac peak loci induced by VitD (Fig. 5b and Extended Data Fig. 8b). VDR, c-JUN, STAT3 and BACH2 each bound ~20–40% of genes differentially expressed by VitD, significantly higher than other loci in the genome (Fig. 5c). Indeed, ~60% of DEGs were bound by at least one of these TFs (Fig. 5d), half of which were bound by more than one (Fig. 5e). Genes bound by two or more TF included STAT3, IL10 and BACH2 (Fig. 5f), indicating the complexity of gene regulation downstream of VitD exposure and interaction of multiple TFs within a gene regulatory network (Fig. 5g). Collectively, these data showed reshaping of the epigenome by VitD, generating new and augmenting existing enhancers and recruitment of transcriptional regulators to these loci to modify transcriptional output. BACH2, IL10 and STAT3 were exemplars of loci at which VDR binding generated new SEs, to which c-JUN, BACH2 and STAT3 were recruited (Fig. 5h and Extended Data Fig. 8c,d) and transcriptional output was increased (Fig. 3b,c).

a, Histograms (top) and heat maps of c-JUN, VDR, STAT3 and BACH2-bound loci in carrier and VitD-treated helper T cells, centered on the peaks. P values by two-sample Kolmogorov–Smirnov test comparing carrier to VitD are shown. b, Histograms of c-JUN, VDR, STAT3 and BACH2-bound loci centered on VitD-induced H3K27Ac peaks. P values by two-sample Kolmogorov–Smirnov test comparing carrier to VitD are shown. c, Proportion of genes differentially expressed after VitD treatment (DEGs from n = 3 experiments) bound by each indicated TF. ****P < 0.0001 by two-sided Fisher exact test compared to all genes. d, Proportion of DEGs bound by 0, 1, 2, 3 or all 4 of the TFs profiled. e, Venn diagram showing overlap in TF binding between VitD DEGs. f, Heat map of DEGs showing binding of genes by c-JUN, VDR, STAT3 and BACH2. Select genes have been highlighted (right). g, Network diagram showing TF binding of genes differentially expressed after VitD treatment. Arrows join TFs to bound genes. Heat map scale indicates FC expression after VitD treatment compared to carrier. h, Genome browser tracks at the BACH2 and IL10 loci showing H3K27Ac, c-JUN, BACH2, STAT3 and VDR binding in carrier and VitD-treated cells. Red and blue dots represent peaks in carrier and VitD-treated cells, respectively. SE denotes super-enhancer regions. Track heights are indicated on the left corner for each track. i, ChIP–qPCR for VDR or IgG in VitD-treated helper T cells from two donors. Anti-VDR ChIP fragments were probed by qPCR for enrichment of promoters of CYP24A1 (left), STAT3 (middle) and IL6 (right). Data are shown separately for each donor; bars show mean + s.e.m. of qPCR. All P values are from two-sided tests.

Source data

Full size image

We noted that STAT3 is directly bound by VDR (Fig. 5f,g and Extended Data Fig. 8d), but we did not find a CUT&Tag VDR peak proximal to the IL6 locus. This may be because IL6 is a lower affinity target, has a distal VDR binding site or because VDR binds this site earlier than the time point at which we carried out CUT&Tag. Thus, because ChIP–qPCR is more sensitive than genome-wide techniques when applied to individual loci, we performed qPCR for STAT3 and IL6 promoters, as well as CYP24A1 (a positive control locus), in anti-VDR ChIP fragments (Fig. 5i). We found strong enrichment of CYP24A1 and STAT3 promoters and moderate enrichment of the IL6 promoter in anti-VDR ChIP fragments, indicating that these loci are all directly bound by VDR and that VDR binding at IL6 is at lower affinity than the other two loci (Fig. 5i). In summary, these data indicated VitD-induced dynamic changes in genome-wide enhancer architecture and recruitment of several TFs to loci that could explain ~60% of the VitD-dependent variance in gene expression.

BACH2 regulates the VitD response in CD4+ T cells

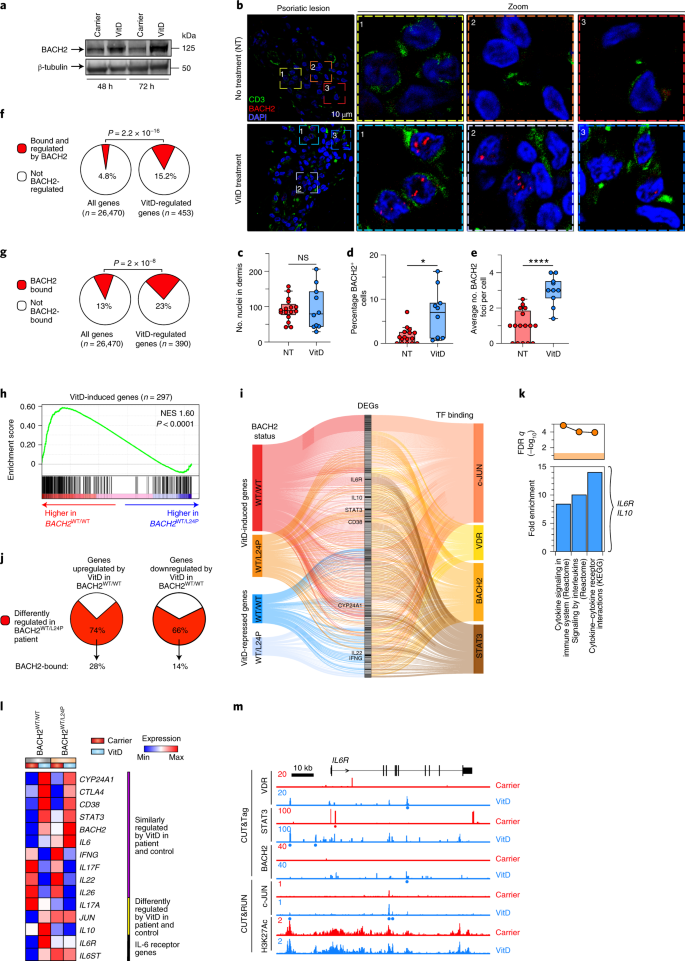

BACH2 is a critical immunoregulatory TF38,39. We confirmed that VitD induces BACH2 protein expression in helper T cells (Fig. 6a). Psoriatic skin is rich in CD4+ T cells, psoriasis severity is associated with low active VitD levels40 and is frequently treated successfully with VitD41. We therefore performed confocal imaging on the dermis of patients with psoriasis treated, or not, with VitD. VitD treatment significantly increased numbers of BACH2+ cells and greater numbers of intranuclear foci of BACH2, compared to untreated skin (Fig. 6b–e), confirming that BACH2 is induced by VitD in vivo. Genes regulated by VitD were ~two- to threefold enriched for BACH2 binding than those not regulated by VitD (Fig. 6f,g). Indeed, BACH2-induced genes and BACH2-repressed genes were more highly expressed in VitD-treated and carrier-treated cells, respectively (Extended Data Fig. 9a,b), indicating a BACH2 signature in VitD-regulated genes. Among the most highly enriched in the leading edge of BACH2-induced genes was the IL-6 receptor α-chain (IL6R) (Extended Data Fig. 9a,c). These observations suggested that a significant proportion of VitD-driven transcription is BACH2-dependent. Thus, we compared transcriptomes of VitD-treated helper T cells from a healthy control (BACH2 WT/WT) to those from a BACH2 haploinsufficient patient (BACH2 WT/L24P)36. VitD-induced genes were significantly enriched in the transcriptomes of wild-type cells (Fig. 6h and Supplementary Table 5a), indicating that normal BACH2 concentrations are required for appropriate regulation of VitD-induced genes (Extended Data Fig. 9e). The same pattern of enrichment was not found for VitD-repressed genes (Extended Data Fig. 9d), potentially indicating that half-normal concentrations of BACH2 are sufficient for repression of VitD targets. Thus, some, but not all, type 1 and type 17 inflammatory cytokines (IFNG and IL17F, but not IL17A) were repressed by VitD in BACH2 haploinsufficient cells (Extended Data Fig. 9e and Supplementary Table 5b).

a, BACH2 Immunoblot in VitD- and carrier-treated helper T cell lysates. Shown is a representative example from n = 3 experiments. b–e, Representative dermal images of lesional skin from psoriasis patients with (n = 2) and without (n = 3) VitD supplementation stained for BACH2 (red) and CD3 (green), showing overview (left-most) and zoomed images (right three images) (b), number of nuclei per image (c), percentage of BACH2+ cells relative to nuclei frequency/image (d) and average number of BACH2 foci per cell (e). For c–e, 5–6 images were acquired for each sample and are shown as median values, with minimum, maximum, 25% and 75% quartiles. f,g, Pie charts comparing percentage of VitD-regulated genes bound and regulated by mouse (f) or human BACH2 (g) against all genes in the genome. The two-sided Fisher exact P value is shown. h, GSEA showing enrichment in VitD-induced genes comparing transcriptomes of VitD-treated wild-type control (BACH2WT/WT) with BACH2-haploinsufficient helper T cells (BACH2WT/L24P). Shown is the empirical P value; NES, normalized enrichment score. i, Sankey diagram showing the relationship between genes up- and downregulated by VitD in BACH2 BACH2WT/L24P compared to BACH2WT/WT helper T cells and the binding of those genes by c-JUN, VDR, BACH2 and STAT3. j, Pie charts comparing percentage of genes up- and downregulated by VitD in BACH2 sufficient cells that are differently regulated in BACH2 haploinsufficiency. The percentage of those genes bound by BACH2 are shown underneath. k, Top three enriched MSigDB canonical pathways pertaining to the genes bound by BACH2 and differently regulated in BACH2-haploinsufficient cells. Indicated are three relevant genes contributing to enriched pathways. l, Heat map showing expression patterns of select VitD-regulated genes in the transcriptomes of carrier- and VitD-treated BACH2WT/WT and BACH2WT/L24P helper T cells. m, Genome browser tracks at IL6R locus showing H3K27Ac, c-JUN, BACH2, STAT3 and VDR binding in carrier and VitD-treated cells. Red and blue dots represent peaks in carrier and VitD-treated cells, respectively. Track heights are indicated (left). In vitro T cell experiments depicted were activated with anti-CD3 + anti-CD28. NS, not significant; *P < 0.01; ****P < 0.0001 by unpaired two-tailed t-test.

Full size image

To better understand the VitD transcriptional regulatory network, we integrated VitD up- and downregulated genes in BACH2 WT/WT and BACH2 WT/L24P CD4+ T cells together with TF binding from CUT&Tag and CUT&RUN (Fig. 6i). The 75% and 66% of genes normally up- and downregulated by VitD, respectively, were not regulated by VitD in BACH2 haploinsufficient cells. Of these, 28% and 14%, respectively, were directly bound by BACH2 (Fig. 6j) and functionally annotated as cytokine and cytokine–cytokine receptor signaling genes, including IL6R and IL10 (Fig. 6k). As noted, VitD promoted IL-10 via IL-6 signaling through IL-6R and STAT3 (Fig. 3f–j). Despite higher basal messenger RNA, IL6 was still induced by VitD when BACH2 levels were sub-normal, but IL10 was not, signifying that the IL-6–STAT3–IL-10 axis was disrupted in BACH2 haploinsufficiency (Fig. 6i–l and Extended Data Fig. 9e). Indeed, IL6R was not appropriately induced when BACH2 levels were sub-normal (Fig. 6i–l and Extended Data Fig. 9e). In animals, the IL6r gene is a direct genomic target of Bach2 and Bach2 knockout status significantly impairs expression of Il6r (Extended Data Fig. 9f). Similar binding of this gene by BACH2 was evident in human cells (Fig. 6m), presumably explaining why BACH2 haploinsufficiency impaired IL6R expression. As BACH2 also binds IL10 (Fig. 5h), it is likely that BACH2 deficiency also contributes directly to lower VitD-induced IL10 transcription. Collectively, these data indicate that BACH2 is a VitD-induced protein regulating a significant portion of the VitD transcriptome, with a key role in mechanisms that stimulate expression of IL-10.

VitD is predicted to retract the TH1 program in COVID-19

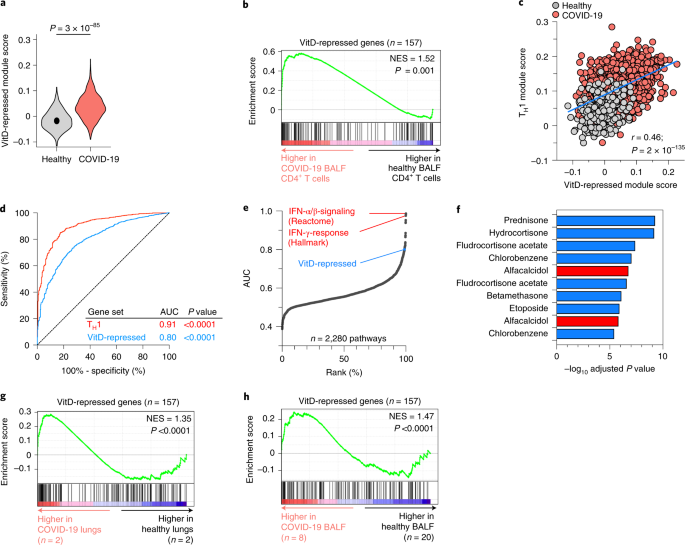

There is compelling epidemiological association between incidence and severity of COVID-19 and VitD deficiency/insufficiency19, but the molecular mechanisms remain unknown. Given preferential TH1 polarization in COVID-19 BALF (Fig. 1d and Extended Data Fig. 1e), we hypothesized that VitD could be mechanistically important for hyper-inflammation in COVID-19 and may be a therapeutic option. We studied expression of VitD-regulated genes (Fig. 3a and Supplementary Table 2b) in COVID-19 BALF helper T cells. Expression of VitD-repressed genes, summarized as module score, was significantly higher in patient helper T cells than healthy controls (Fig. 7a). This was further corroborated by gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) showing that genes more highly expressed in patient compared to control cells were enriched in VitD-repressed genes (Fig. 7b). On a per-cell basis the VitD-repressed module score correlated strongly with the TH1 score in BALF helper T cells (Fig. 7c), indicating a reciprocal relationship between TH1 genes and VitD-repressed genes. By contrast, VitD-induced genes were not substantially different (Extended Data Fig. 10a), nor were VitD-regulated genes different in PBMCs of patients compared to healthy donors (Extended Data Fig. 10b). To assess the ability of the TH1 and VitD-repressed gene signatures to distinguish patient from healthy BALF helper T cells on a per-cell basis, we constructed receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves of the module scores. The area under the curve (AUC) for the two scores were 0.91 and 0.80, respectively (P < 0.00001 for both) (Fig. 7d). Thus, both TH1 and VitD-repressed gene signatures were strong features of COVID-19 BALF helper T cells. To contextualize these performances, we calculated AUCs for module scores of every gene set in Hallmark and canonical pathways curated by the Molecular Signatures Database (MSigDB) (n = 2,279 gene sets). The top performing sets were IFN responses, as expected. The performance of the VitD-repressed gene set was within the top 1% of all gene sets (Fig. 7e and Supplementary Table 6), indicating that this was among the very best performing gene sets. We then predicted significant drugs (among n = 461) potentially able to counteract genes upregulated in COVID-19 BALF helper T cells. Five of the top ten most significant drugs were steroids and two were VitD (alfacalcidol) (Fig. 7f and Supplementary Table 7). These were corroborated in independent datasets by GSEA, showing genes more highly expressed in lung biopsies or bulk BALF RNA-seq of COVID-19 compared to healthy control to be enriched in VitD-repressed genes (Fig. 7g,h). Significant numbers of genes modulated by VitD were shared by corticosteroid targets (Extended Data Fig. 10c). Steroids, including dexamethasone, increase transcription of VDR so may show therapeutic synergism with VitD. Collectively, these data suggest that, in helper T cells from patients with severe COVID-19, the VitD-repressed gene set is de-repressed and that there may be clinical benefit from adding VitD to other immunomodulatory agents (Extended Data Fig. 10d).

a, Violin plots showing expressions of VitD-repressed genes, summarized as module scores, in BALF helper T cells of patients with COVID-19 and healthy controls. Exact P values in a have been calculated using two-tailed Wilcoxon tests. b, GSEA showing enrichment in VitD-repressed genes within genes more highly expressed in scRNA-seq CD4+ BALF T cells of patients with COVID-19 compared to healthy controls. c, Correlation between module scores of TH1 genes and VitD-repressed genes on a per-cell basis in BALF helper T cells of patients with COVID-19 and healthy controls. Pearson r and exact P values are shown. d, ROC curve, evaluating the performance of the TH1 and VitD-repressed module scores to distinguish BALF helper T cells of patients with COVID-19 from healthy controls. Shown are the AUC statistics and P values. e, Analyses showing the performance of all MSigDB canonical and Hallmark gene sets to distinguish BALF helper T cells of patients with COVID-19 from healthy controls, ranked by AUC values. Marked are the top two performing gene sets in red and the position of the VitD-repressed gene set within the top 1% of all gene sets. f, Top ten drugs predicted (out of 461 significant drugs) to counteract genes induced in BALF helper T cells of patients with COVID-19 compared to healthy controls, ordered by adjusted P value. Highlighted in red is alfacalcidol, a US Food and Drug Administration-approved active form of VitD. g,h, GSEA showing enrichment in VitD-repressed genes for genes more highly expressed in bulk RNA-seq lung biopsy specimens (g) and bulk RNA-seq BALF cells (h) of COVID-19 compared to healthy controls. Empirical P values are shown for GSEA in b,g,h. P values in d are from the Mann–Whitney U-statistic. Data in a–f are from n = 8 patients with COVID-19 and n = 3 healthy controls, sourced from GSE145926 and GSE122960. Data in g,h are from GSE147507 and HRA000143, respectively and n numbers are indicated.

Full size image

Discussion

We showed that cell-intrinsic complement orchestrates an autocrine/paracrine autoregulatory VitD loop to initiate TH1 shutdown. VitD causes genome-wide epigenetic remodeling, induces and recruits TFs, including STAT3, c-JUN and BACH2, which collectively repress TH1 and TH17 programs and induce IL-10 via IL-6–STAT3 signaling. This program is abnormal in lung helper T cells of patients with severe COVID-19, which show preferential TH1 skewing and could be potentially exploited therapeutically by using VitD as an adjunct treatment.

IFN-γ-producing airway helper T cells are key components of immunity to coronaviruses, including SARS-CoV1 and MERS-CoV20. TH1-polarized responses are also a feature of SARS-CoV2 in humans24 and severe COVID-19 is accompanied by prolonged, exacerbated, circulating TH1 responses21. Complement receptor signaling is a driver of TH1 differentiation and required for effective antiviral responses12,42. C3 cleavage generates C3b, which binds CD46 on T cells. We have previously shown that the lungs in COVID-19 are a complement-rich microenvironment, that local CD4+ T lymphocytes have a CD46-activated signature13 and show here that these T cells are TH1-polarized. Pro-inflammatory function is important for pathogen clearance, but a switch into IL-10 production is a natural component during successful transition into the TH1 shutdown program and reduces collateral damage16. Inability to produce IL-10 results in more efficient clearance of infections but severe tissue damage from uncontrolled TH1 responses results in death2. The benefits of remediating inflammatory pathways in severe COVID-19 is demonstrated by successful trials of dexamethasone, an immunosuppressive drug that reduces mortality1.

VitD has pleiotropic functions in the immune system, including antimicrobial as well as regulatory properties, which are cell- and context-dependent43,44. VitD deficiency is associated with higher prevalence and worse outcomes from infections, including influenza, tuberculosis and viral upper respiratory tract illnesses17, as well as autoimmune diseases, including type 1 diabetes, multiple sclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis and inflammatory bowel disease18. Helper T cells play key roles in all these diseases. Thus, understanding VitD biology in helper T cells has potential translational impact.

Our data indicate the complexities of TFs working within networks to regulate sets of genes. After VitD ligates VDR, c-JUN, STAT3 and BACH2 are recruited to acetylated loci, shaping the transcriptional response to VitD. c-JUN is a member of the AP-1 basic leucine zipper family, primarily involved in DNA transcription45. This TF was bound adjacent to 40% of VitD-regulated coding loci. BACH2 is a critical immunoregulatory TF38,39 downregulated in lesional versus non-lesional psoriatic skin46. Active VitD concentrations inversely correlate with severity of psoriasis40. We found that VitD treatment of psoriatic lesional skin upregulated BACH2 expression. Both haploinsufficiency and single nucleotide variants of BACH2 associate with monogenic and polygenic autoimmunity, respectively, in humans36,47. No BACH2 knockout humans have yet been identified, suggesting incompatibility of complete BACH2 deficiency with life. Indeed, Bach2 –/– mice succumb to fatal autoimmunity. We found that loss of even 50% of the normal cellular concentration of BACH2 in the haploinsufficient state substantially altered (~70% of) the VitD-regulated transcriptome. As only a proportion of these genes were directly BACH2-bound, it is probable that BACH2 is a requisite for normal recruitment and function of the other transcriptional regulators.

Both the incidence and severity of COVID-19 are epidemiologically associated with VitD deficiency/insufficiency19, but the molecular mechanisms remain unknown. We found a link between the inflammatory TH1 program and a VitD-repressed gene set. Attempts to study CD4+ T cells from the site of inflammation were unsuccessful due to the rapid apoptosis of patient cells, but our in silico analyses suggest either dysregulation of the VitD program in COVID-19 or that simple deficiency/insufficiency of substrate (VitD) might explain the epidemiological association.

IL-6 is a pleiotropic, often pro-inflammatory, cytokine. IL-6 is implicated in the COVID-19 'cytokine storm' and targeting of this cytokine specifically has proved beneficial to patients32. Our data suggest that pro-inflammatory IL-6 functions may be redirected to production of anti-inflammatory IL-10 by VitD in activated human helper T cells. VitD supplementation in children significantly increases serum IL-6 (and nonsignificantly increases IL-10)48 indicating that these observations may also occur in vivo. In the skin, where VitD concentrations are high, IL-6 overexpression protects from injurious stimuli or infection49 and IL-6-deficiency impairs wound healing50. Moreover, an adverse effect of anti-IL-6R for treating inflammatory arthritis is idiosyncratic development of psoriasis51, indicating a tolerogenic role for IL-6 at this site. Thus, adjunct VitD therapy in severe COVID-19 could potentially divert pro-inflammatory and induce anti-inflammatory effects of IL-6, which may be an alternative to blocking IL-6R signaling.

These data identified the VitD pathway as a potential mechanism to accelerate shutdown of TH1 cells in severe COVID-19. From experience in other diseases, it is likely that VitD will be ineffective as monotherapy. Combination therapy could potentially ameliorate significant adverse effects of other drugs, for example high-dose corticosteroids, including over-immunosuppression or metabolic side-effects. An important consideration of VitD therapy in COVID-19 is stimulation of IL-6 production from CD4+ T cells. Although autocrine/paracrine IL-6 induces IL-10 in these cells, IL-6 could potentially have pro-inflammatory properties on other cells. These possibilities may be mitigated by adding VitD as an adjunct to other immunomodulators, such as corticosteroids or JAK inhibitors13. Of note, two randomized clinical trials with calcifediol, a VitD analog with high bioavailability not requiring hepatic 25-hydroxylation, comprising >1,000 patients together, reported reductions in risk of intensive-care unit admission or death when used in addition to standard care (odds ratio of 0.13 and 0.22, respectively52,53). These findings are not necessarily specific to COVID-19, as VitD can protect against acute respiratory tract infections in general17.

In conclusion, we identified an autocrine/paracrine VitD loop permitting TH1 cells to both activate and respond to VitD as part of a shutdown program repressing IFN-γ and enhancing IL-10. These events involved significant epigenetic reshaping and recruitment of a network of key TFs. These pathways could potentially be exploited therapeutically to accelerate the shutdown program of hyper-inflammatory cells in patients with severe COVID-19.

Methods

Ethics approvals

Human studies, conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, were approved by the Institutional Review Board of Guy's Hospital (reference 09/H0707/86), National Institutes of Health (NIH) (approval nos. 7458, PACI, 13-H-0065 and 00-I-0159) and Imperial College London (approval no. 12/WA/0196 ICHTB HTA license number 12275 to project R14098). All patients provided informed written consent.

Human T cell isolation and culture

Human PBMCs were purified from anonymized leukodepletion cones (Blood Transfusion Service, NHS Blood and Transplantation) or healthy volunteer whole blood packs/buffy coats from the NIH Blood Bank and from fresh patient blood. Leukodepletion cones were diluted 1:4 with PBS and layered onto Lymphoprep (Axis-Shield). Whole blood packs/buffy coats were diluted 1:2 with PBS onto Lymphocyte Separation Medium (25-072-CV LSM, Corning) and centrifuged.

CD4+CD25– cells were used throughout, unless specified. CD4+ T cells were enriched using RosetteSep Human CD4+ enrichment cocktail (StemCell) with CD4+CD25– cells obtained by depletion of CD25+ T cells using CD25-positive selection (CD25 microbeads II, Human, Miltenyi Biotec) followed by unlabeled cell collection. Human memory CD4+ T cells were used for RNA-seq, CUT&RUN and CUT&Tag experiments as these cells express the VDR. These cells were isolated from PBMCs using Miltenyi Memory CD4+ T cell Isolation Kit Human (130091893) or StemCell EasySep Human Memory CD4+ T Cell Enrichment kit (19157) or by flow sorting.

For flow sorting, bulk CD4+ T cells were enriched as above then stained with antibodies against CD4 (OKT4, Thermo Fisher Scientific), CD45RA (HI100, BioLegend), CD45RO (UCLH1, BD Biosciences) and CD25 (2A3, BD Biosciences) in MACS buffer at 4 °C for 30 min. CD4+CD25–CD45RO+CD45RA– memory cells were sorted into medium to >99% purity by a FACSAria (BD Biosciences). Sorting strategy and representative post-sort purities are shown in Extended Data Fig. 10e.

Cells were cultured in X-VIVO-15 Serum-free Hematopoietic Cell Medium (04-418Q, Lonza) supplemented with 50 IU ml−1 penicillin, 50 μg ml−1 streptomycin and 2 mM l-glutamine (Gibco), at 37 °C 5% CO2 in a non-tissue culture-treated 96-well U-bottom plate (Greiner) at a density of 106 cells ml−1 in 200 μl. Cells were activated using Human T-Activator CD3/CD28 Dynabeads (11131D, Gibco, cell to bead ratio of 4:1). Where indicated, cells were plate-activated in non-tissue culture-treated 48-well plates (Greiner) pre-coated with anti-CD3 (OKT3, from Washington University hybridoma facility), anti-CD3 + anti-CD28 (CD28.2, Becton Dickinson) or anti-CD3 + anti-CD46 (TRA-2-10, a gift from J. P. Atkinson, Washington University), with or without 1 µM cathepsin L inhibitor (ALX-260-133-M001, Enzo Life Sciences), with IL-2 included (50 U ml−1; PeproTech), in a total volume of 250 µl at a density of 5 × 105 per well. Antibody-coated plates were prepared by diluting antibodies (2 μg ml−1) in D-PBS + Ca2+Mg2+ (Gibco) and adding to 48-well plates overnight in a volume of 150 µl per well at 4 °C, subsequently plates were rinsed with PBS before cell suspension addition and centrifugation (swinging-bucket rotor, 300g, 3 min, room temperature). Cells were additionally cultured with 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 (BML-DM200-0050, Enzo Life Sciences) or 25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 (BML-DM100-0001, Enzo Life Sciences), both reconstituted in 99.8% ethanol (Sigma-Aldrich), used at 10 nM unless indicated, with identically diluted ethanol used as carrier control. IL-6 (BioLegend) and tocilizumab (a gift from C. Roberts in L. Taams' laboratory) were used in functional experiments.

Flow cytometry

Cells were stained 30 min at 4 °C in a final volume of 100 μl staining buffer with antibodies against CD4 (OKT4, Thermo Fisher Scientific), IL-6 (MQ2-13A5, BioLegend), LAG-3 (3DS223H, Thermo Fisher Scientific), CD49b (P1H5, Thermo Fisher Scientific) with 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) or LIVE/DEAD Fixable Aqua/Violet (Invitrogen) to exclude dead cells. For intracellular staining, cells were treated with the spiked addition of Phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) (50 ng ml−1, Sigma-Aldrich), ionomycin (1 μg ml−1, Sigma-Aldrich), GolgiStop (1×, BD Biosciences) and brefeldin A (1×, BD Biosciences) to medium then cultured 5 h, subsequently washed in PBS, surface stained, treated with Cytofix/Cytoperm (eBioscience) and subsequent Perm/Wash buffer (eBioscience) steps before incubation with intracellular antibodies for 30 min at 4 °C. Samples were washed and acquired on a LSRFortessa (BD Biosciences) or the Attune NxT Flow Cytometer (Invitrogen) within 24 h and analyzed using FlowJo v.9.9.6. Cell proliferation analysis was carried out by CFSE dilution in polyclonally activated CD4+CD25– T cells with carrier or VitD after 72 h.

Cell proliferation and activation markers were assessed in purified CD4+ cells with cellTrace Violet (CTV; C34556, Invitrogen) and surface staining against CD62L-FITC (MEL-14, BioLegend), CD69-PE-Cy7 (FN50, Invitrogen) or CD25-PE-Cy7 (BC96, Invitrogen) and LIVE/DEAD fixable near-IR (Invitrogen).

Cytokine measurement

Supernatants from 96-well plates were aliquoted and stored at −20 °C. Cytokines were quantified by the Human/Mouse TH1/TH2/TH17 Cytometric Bead Array (CBA) (BD Biosciences) using a FACSCanto II (BD Biosciences), analyzed by FCAP Array v.3.0 (BD Biosciences). Alternatively, we used the LEGENDplex Human Inflammation Panel 1 (13-plex) (740808, BioLegend) with the Attune NxT Flow Cytometer. Cytokine assays were analyzed by FlowJo v.9.

For intracellular cytokine detection, the IFN-γ/IL-10 Secretion Assay Detection kit (Miltenyi, 130-090-761) was used on live cells after 72 h.

Immunoblotting

Cell extracts were prepared by lysis in RIPA (Thermo Fisher Scientific) including 1:250 diluted Protease Inhibitor Cocktail Set III (Calbiochem) and 5% 2-mercaptoethanol, denatured at 95 °C for 5 min. Protein concentration was quantified using the Quick Start Bradford Protein Assay (Bio-Rad). Proteins resolved by SDS–PAGE on 10% Tris-glycine (Invitrogen) were transferred onto polyvinylidene fluoride membranes (Millipore) via a XCell II Blot Module (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Immunoblotting was performed with blocking in PBS + 10% w/v Blotting-Grade Blocker (1706404, Bio-Rad) for VDR, STAT3 and c-Jun or 3% w/v BSA (Sigma-Aldrich) for pSTAT3 and phospho-c-Jun made up in PBS + 0.1% v/v Tween20 (Sigma-Aldrich) then incubated overnight with antibodies against VDR (1:100 dilution, D-6, Santa Cruz), pSTAT3 (1:2,000 dilution, D3A7, Cell Signaling Technologies), STAT3 (1:1,000 dilution, 124H6, Cell Signaling Technologies), phospho-c-Jun (1:1,000 dilution, S63, R&D Systems) or c-Jun (1:2,000 dilution, L70B11, Cell Signaling Technologies), followed by 2 h incubation with HRP-conjugated anti-mouse or anti-rabbit antibodies (1:1,000 dilution, TrueBlot, Rockland), then washed with PBS + 0.5% v/v Tween20. Targets were detected using ECL-Plus (Thermo Fisher Scientific), visualized by ImageQuant LAS 4000 mini (GE Healthcare) and quantified (Image Studio Lite, LI-COR).

Nuclear and cytoplasmic extracts were isolated (NE-PER Nuclear and Cytoplasmic Extraction, Thermo Fisher Scientific) and purity was determined by immunoblotting against HSP90 (1:2,000 dilution, C45G5, Cell Signaling Technologies) and H2A.X (1:1,000 dilution, D17A3, Cell Signaling Technologies).

For BACH2, snap-frozen cell pellets of 6 × 105 cells were resuspended directly in Laemmli + 5% 2-mercaptoethanol (Bio-Rad) and denatured (95 °C for 5 min), cooled at room temperature, loaded and resolved at 120 V on a Criterion TGX Gel (Bio-Rad). Gel-bound proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose (Trans-Blot Turbo Midi, Bio-Rad) via a Trans-Blot Turbo (Bio-Rad). Membrane blocking occurred (PBS Odyssey Blocking Buffer, LI-COR) before addition of BACH2 (D3T3G, Cell Signaling Technologies) antibody in blocking buffer (1:5,000 dilution) then rotated overnight at 4 °C. Membranes were washed three times (PBS + 0.1% Tween20) and exposed to IRDye 800CW goat anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody (926-32211, LI-COR) in blocking buffer (1:5,000 dilution) for 1 h at room temperature. After three washes, antibody signals were visualized (Odyssey CLx, LI-COR). The membrane was re-probed with anti-β-tubulin diluted in blocking buffer (2146, Cell Signaling Technologies, 1:1,000 dilution) and quantified (Image Studio v.5.2, LI-COR).

Human phospho-kinase antibody array

Proteome Profiler Human Phospho-Kinase Array (R&D Systems) was carried out on VitD- or carrier-treated CD4+ cells. Cells were lysed in manufacturer's buffer, protein concentrations quantified by Quick Start Bradford Protein Assay (Bio-Rad) and samples adjusted to 800 μg ml–1 with lysis buffer. Then, 334 μl was loaded per membrane and signals were amplified by Chemi-Reagent Mix imaged (ImageQuant LAS 4000 mini) and quantified (Image Studio Lite). Reference spots were used to normalize signals across membranes.

VDR and DAPI colocalization

VDR and DAPI colocalization was performed in CD4+ T cells stained with VDR antibody (1:250 dilution, D-6), anti-mouse-AlexaFluor647 (1:400 dilution, clone poly4053, BioLegend) and DAPI. Images were acquired via ImageStreamX running Inspire and VDR to DAPI colocalization assessed (IDEAS v.3.0, Amnis). A minimum of 1 × 105 events were acquired per sample.

Quantitative PCR

The 2–4 × 106 cells were lysed in 350 μl Trizol (Life Technologies) and RNA extracted by Direct-zol Miniprep (Zymo Research) with on-column genomic DNA digest. RNA was quantified by spectrophotometry (NanoDrop) and reverse transcribed (qPCRBIO cDNA Synthesis, PCR Biosystems). qPCR in 384-well plates with SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Life Technologies) was used with the ViiA7 real-time PCR system (Life Technologies). Reactions were carried out in triplicate with 18s and UBC (geNorm 6 gene kit, ge-SY-6, PrimerDesign UK) as a reference alongside IL6 detection (Hs_IL6_1_SG QuantiTect Primer Assay, QIAGEN). TaqMan probes (Applied Biosystems) for CYP27B1 (Hs01096154_m1), VDR (Hs01045843_m1), IFNG (Hs00989291_m1), IL10 (Hs00961622_m1), CTSL (Hs00964650_m1), CYP27B1 (Hs01096154_m1) and 18S (Hs99999901_s1) were utilized on reverse-transcribed RNA (iScript, Bio-Rad) with TaqMan Master Mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The comparative Ct method was used for analysis using Viia7 software producing a Ct (relative quantity compared to a reference sample).

Inhibition and siRNAs

For STAT3 siRNA, memory CD4+ T cells were sorted and rested overnight in culture medium. Then, 5 × 106 cells were washed twice with PBS and nucleofected with 10 nM STAT3 Silencer Select siRNA (s745, sense GCACCUUCCUGCUAAGAUUTT and antisense AAUCUUAGCAGGAAGGUGCCT) or Silencer Select Negative Control (Thermo Fisher Scientific) using the Amaxa Human T Cell Nucleofector kit (Nucleofector 2b Device, U-014 program, Lonza). Nucleofected cells were cultured in medium for 6 h followed by dead cell removal (Lymphoprep, Axis-Shield). Then, 2 × 106 recovered cells were activated with anti-CD3/CD28 beads for 72 h and knockdown was assessed by immunoblot.

For chemical STAT3 inhibition, memory CD4+ T cells were sorted and rested overnight. Then, 2 × 106 cells were activated as before with VitD or carrier and additionally with 150 nM curcubitacin I, Cucumis sativus L. (Calbiochem) or carrier (ethanol) for 72 h.

For VDR, CYP27B1 and CTSL siRNA, total CD4+ T cells were plate-activated with CD3/CD46 antibodies as described above. Dharmacon Accell SMARTPool siRNAs against CYP27B1 (E-009757-00-0005), VDR (E-003448-00-0005), CTSL (E-005841-00-0005), Non-targeting Control (D-001910-01-05) or Green Non-targeting Control (D-001950-01-05) were added to cultures at 1 µM for 72 h with knockdown assessed by qPCR.

H3K27Ac and c-JUN CUT&RUN

CUT&RUN sequencing was performed on memory CD4+ T cells activated as above in the presence of carrier or VitD for 0.75 h, 48 h and 72 h using the published protocol of Skene et al.55. Antibodies against H3K27Ac (ab4729, Abcam), c-JUN (60AB, Cell Signaling Technologies) and nonspecific IgG (31235, Thermo Fisher Scientific) were used with pAG-MNase (123461, Addgene) on 5 × 104 cells per target. CUT&RUN (and CUT&Tag below) buffer components were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich and Thermo Fisher Scientific. Post-CUT&RUN, short DNA fragments were prepared for paired-end sequencing (NEB Ultra II, New England Biolabs) with NovaSeq (Illumina). Amplified libraries were quantified by high sensitivity fluorometry (DeNovix) and sized via the 4200 TapeStation (Agilent Technologies).

H3K27Ac reads were aligned to the human reference genome (GRCh37; hg19) using Bowtie2 (ref. 56) with parameters '–local –maxins 250' with sorting and indexing of aligned reads by SAMtools v.1.10 (ref. 57); reads with mapping quality <30 were removed. H3K27Ac peaks were called by MACS2 (ref. 58) with parameter '-f BAMPE –nomodel'. JUN reads were mapped without '–local' parameter. The <120-bp fragments were further sorted and indexed by SAMtools v.1.10 (ref. 57). JUN-induced peaks were called by MACS2 parameters '–nomodel -g hs -f BAMPE -q 0.01 –SPMR –keep-dup all'. IgG BAM files were included as controls for MACS2. Peaks for H3K27Ac and JUN experiments were screened against previously characterized hypersequencable-regions (Hg19 Blacklist, CutRunTools59). H3K27Ac and JUN mean binding intensities in peak regions were calculated by University of California Santa Cruz bigWigAverageOverBed. Peaks, combined from two conditions, with mean binding intensity >0.2 in at least one condition and FC of signal >1.5 were differential. Known motifs ±100 bp from differential peak summits were identified (HOMER, findMotifsGenome.pl, parameter '-size given'). De novo motif footprinting for c-JUN was performed (CutRunTools74). Average cuts per bp proximal to JUN peaks was plotted as a histogram relative to IgG. CUT&RUN tracks and heat maps were visualized using IGV (Broad Institute) and deepTools60, respectively.

De novo super-enhancer calling

SEs were called using ROSE (Rank Ordering of Super-Enhancers)37. H3K27Ac CUT&RUN VitD-induced peaks were sorted/indexed using SAMtools v.1.10 (ref. 57) and executed with ROSE_main.py with carrier control. SE annotations were screened and corrected if needed. Hockey-stick plots of rank-ordered stitched-enhancers plotted against VitD minus carrier H3K27Ac signal were generated (RStudio v.1.2.5033)

VDR, STAT3 and BACH2 CUT&Tag

VDR, STAT3 and BACH2 genome-wide binding in memory CD4+ T cells activated in the presence of 10 nM VitD or carrier for 96 h was detected by CUT&Tag as per the published protocol (CUT&Tag v.3, https://doi.org/10.17504/protocols.io.bcuhiwt6)61 using fixed nuclei (2 min fixation of isolated nuclei at room temperature) with 75,000 nuclei per target and antibodies targeting either VDR (D2K6W, Cell Signaling Technologies), STAT3 (D3Z2G, Cell Signaling Technologies), BACH2 (D3T3G) or nonspecific IgG (31235) diluted 1:50 accordingly and incubated with fixed nuclei for 1 h at room temperature. Secondary antibody (1:100 dilution) (ABIN101961, antibodies-online) was bound for 0.5 h at room temperature. Preloaded pA-Tn5 (C01070001, Diagenode) was tethered to antibodies for 1 h at room temperature. Libraries were sequenced as paired-ends by NovaSeq. Resulting reads were processed and mapped to Hg19 (CutRunTools), with peaks called (SEACR v.1.2, stringent, all mapped fragments at https://github.com/FredHutch/SEACR) and hypersequencable-regions subtracted. Known motif enrichment was determined ±200 bp from peak summits and data were visualized as in CUT&RUN.

VDR ChIP–PCR

ChIP–PCR detection of VDR binding at the promoters of CYP24A1, STAT3 and IL6 was determined from 2 × 105 CD4+ cells activated with VitD or carrier for 48 h followed by True MicroChIP (C01010132, Diagenode; three bioruptions per sample). Then, 4 µg of anti-VDR (D-6) or IgG2a isotype control antibody (E5Y6Q, Cell Signaling Technologies) was used during overnight chromatin precipitation at 4 °C before reverse-crosslinking and purification (MicroChIP DiaPure, Diagenode). qPCR primers were designed to amplify regions within 500 bp upstream of the transcriptional start site for each respective gene: CYP24A1 (F: TGACCGGGGCTATGTTCG, R: GGCTTCGCATGACTTCCTG); STAT3 (F: CTGTTCCGACAGTTCGGTGC, R: GCAGGACATTCCGGTCATCTTC); and IL6 (F: GTAAAACTTCGTGCATGACTTCAGC, R: GGGGGAAAAGTGCAGCTTAGG). Triplicate qPCR using POWRUP SYBR Green (Thermo Fisher) was quantified via CFX384 (Bio-Rad) and results calculated as %Input = 2(−ΔCt (normalized ChIP)).

RNA sequencing and analysis

Memory CD4+ T cells, including from BACH2WT/L24P patients, were activated with VitD or carrier. Then, 6 × 105 cells were pelleted at 300g for 5 min and RNA was extracted by RNAqeous Micro (Thermo Fisher Scientific). RNA at 1 μg total for each sample was subjected to NEBNext Poly(A) mRNA Magnetic Isolation (E7490) and resulting mRNA was prepared for RNA-seq by NEB Ultra II (New England Biolabs) and sequenced by HiSeq (Illumina).

The expression levels of all genes in RNA-seq libraries were quantified by 'rsem-calculate-expression' in RSEM v.1.3.1 (ref. 62) with parameters '–bowtie-n 1 –bowtie-m 100 –seed-length 28 –bowtie-chunkmbs 1,000'. The bowtie index for RSEM alignment was generated by 'rsem-prepare-reference' on all RefSeq genes, downloaded from University of California Santa Cruz Table Browser in April 2017. EdgeR v.3.26.8 (ref. 63) was used to normalize gene expression among all libraries and identify DEGs among samples. Microarray analysis sourced from GSE119416 was carried out using Partek Genomics Suite (Partek). DEGs were defined using the following criteria: at least 1.5 × FC in either direction at P < 0.05 for microarray; at least 1.75 × FC in either direction at FDR < 0.05 for RNA-seq.

Single-cell RNA sequencing and analysis

COVID-19 bronchoalveolar lavage dataset

The pre-processed h5 matrix files for nine bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) samples from patients with COVID-19 and four healthy control BAL samples were from GSE145926 (ref. 64), GSE122960 (ref. 65) and GSM3660650, respectively. Read mapping and basic filtering performed with Cell Ranger (10X Genomics). Further processing using Seurat v.3 (ref. 66) was performed as follows: only genes found to be expressed in >3 cells and cells with gene number between 200 and 6,000 (unique molecular identifier (UMI) count >1,000) were retained. Cells with >10% of their UMIs mapping to mitochondrial genes or cells with <300 features were discarded to eliminate low-quality cells. Filtering yielded 66,453 cells across 12 samples. Filtered count matrices were normalized by total UMI counts, multiplied by 10,000 and transformed to natural log space. Top 2,000 variable features determined by the variance stabilizing transformation function (FindVariableFeatures) using default parameters. Data were integrated using canonical correlation analysis (FindIntegrationAnchors/IntegrateData) with parameter k.filter = 140 (ref. 67). Variants arising from library size and percentage of mitochondrial genes were regressed out (ScaleData, Seurat). Principal-component analysis (PCA) was performed and the top 50 principal components (PCs) were included in a UMAP. Clusters identified on a shared nearest neighbor (SNN) modularity graph using the top 50 PCs and the original Louvain algorithm. Cluster annotations are based on canonical marker genes.

Cells identified as 'T' and 'cytotoxic T' were subsetted and re-processed. Samples C146 and C52 were removed due to low T cells (19 and 56 cells, respectively). Integration was performed using FindIntegrationAnchors/IntegrateData with parameters: 'dims = 1:30 k.filter = 124'. Normalization, variable feature detection, scaling, dimensionality reduction and clustering were performed using the top 30 PCs and clustering resolution of 0.3. Annotation was guided by marker genes (Extended Data Fig. 1c). The contaminating macrophage cluster annotated by canonical marker genes (for example CD14) was removed. Statistical differences were assessed by two-tailed Wilcoxon test. DEGs were defined by FC > 1.5, adjusted P value <0.05 and expression in at least 10% of cells in either cluster comparison.

Two clusters were annotated as CD4+ T cells, one with few cells but expressed similar markers to the main CD4+ cluster. The two were combined and considered together for analysis. DEGs between COVID-19 and healthy CD4+ T cells were visualized using Morpheus (https://software.broadinstitute.org/morpheus/). DEGs upregulated in COVID-19 CD4+ T cells were subjected to pathway analysis (Fig. 1c) using the Hallmark gene set collection from MSigDB (v.7.1) or drug prediction from the National Toxicology Program's DrugMatrix gene sets (n = 7,876) using EnrichR (Fig. 4f). Gene list scores were calculated by the AddModuleScore function in Seurat with a control gene set (n of 100). Correlations and ROC analyses on module scores comparing patients and healthy controls were performed in R or Prism v.8.4.0.

COVID-19 PBMC dataset

The pre-processed R objects for six PBMC samples from patients with COVID-19 and six healthy control PBMC samples were from GSE150728 (ref. 68) with read mapping and filtering performed using Cell Ranger. The exon count matrices were further processed by Seurat as follows: only genes found to be expressed in more than ten cells were retained. Quality control steps for filtering the samples were performed as described previously68. Cells with 1,000–15,000 UMIs and <20% of reads from mitochondrial genes were retained. Cells with >20% of reads mapped to RNA18S5 or RNA28S5 and/or expressed >75 genes per 100 UMIs were excluded. The SCTransform function was used to normalize the dataset and to identify variable genes68. PCA was performed and the top 50 PCs were included in UMAP dimensionality reduction. Clusters were identified on an SNN modularity graph using the top 50 PCs and the original Louvain algorithm. Cluster annotations were based on canonical marker genes. Gene list module scores were calculated using the AddModuleScore function in Seurat66. AUCs for module scores of every gene set in Hallmark and canonical pathways were curated by MSigDB (n = 2,279 gene sets)69,70,71.

Gene set enrichment analysis and gene lists

GSEA was carried out as published69. Tr1 gene lists were obtained from GSE139990. Data were filtered to include only genes expressed at >0.25 counts per million in at least two samples. Trimmed mean of M values (TMM) were normalized within edgeR v.3.28.1 and differential expression was performed using glmQLFit and glmQLFTest edgeR functions. Tr1 signatures were defined as DEGs (at least fourfold change in either direction at FDR < 0.05) between Tr1 and TH0 cells. TH1/TH2/TH17 gene lists were obtained from transcriptomes of sorted mouse CD4+ T cell subsets72. VitD-regulated genes were defined as described in RNA-seq methods. BACH2-bound and regulated genes were obtained from GSE45975 (ref. 38). All gene lists used in this manuscript are in Supplementary Table 8.

Psoriasis lesional skin staining, imaging and analysis

Informed consent for all patients with psoriasis and data were obtained under the Psoriasis, Atherosclerosis and Cardiometabolic Disease Initiative (PACI, 13-H-0065). Samples included three patients with psoriasis not on VitD and two patients with psoriasis on VitD supplementation. Three-millimeter punch-biopsies were collected from psoriasis lesional skin and placed into 10% formalin. Seven-micrometer skin sections were mounted on glass slides, de-waxed and antigens were retrieved via the citrate buffer method. Sections were washed once in PBS and blocked for 20 min at room temperature in 10% normal goat serum then stained with anti-CD3 (1:50 dilution, F7.2.38, Thermo Fisher Scientific) and anti-BACH2 (1:40 dilution, D3TG) primary antibodies overnight at 4 °C. The next day sections were washed in 0.01 M PBS and Alexa Fluor 488 and Alexa Fluor 594 (1:100 dilution, Jackson Immuno Research Laboratories, 115-546-062 and 111-586-047), secondary antibodies were added for 1 h at room temperature and then sections were washed in 0.01 M PBS. Hoechst was added to the samples for 10 min, then samples were washed and cover-slipped with Fluoromount G. Images were collected on a Zeiss 780 inverted confocal microscope at ×40 with oil immersion and analyzed (ImageJ). Representative images were prepared in Zen Blue v.3.1 (Zeiss). For each sample, 5–6 images were acquired. To quantify the frequency of immune cells in the dermis, images were cropped to 1,200 × 1,200 pixels to exclude the epidermis and nuclei numbers in the 408 nm channel were determined. The number of BACH2-positive cells in the 594 nm channel were calculated per image and the number of BACH2 foci per BACH2-positive cell were recorded.

Data presentation and statistical analysis

Figures were prepared using Adobe Illustrator (Adobe). Statistical analysis and graphical visualizations were carried out in GraphPad Prism (v.8.4.0), XLstat Biomed (v.2017.4), DataGraph v.4.5.1 (Visual Data Tools), Cytoscape 3 (ref. 73) and Circos Table Viewer v.90.63.9 (ref. 74). Statistical analyses were performed using appropriate paired or unpaired parametric and nonparametric tests, as required. Multiple comparisons were performed using ANOVA. P values <0.05 were considered statistically significant throughout.

Reporting Summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

Data generated for this study are deposited at the Gene Expression Omnibus under GSE154741. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

- 1.

RECOVERY Collaborative Group et al.Dexamethasone in hospitalized patients with COVID-19. New Engl. J. Med. 384, 693–704 (2020).

Google Scholar

- 2.

Gazzinelli, R. T. et al. In the absence of endogenous IL-10, mice acutely infected with Toxoplasma gondii succumb to a lethal immune response dependent on CD4+ T cells and accompanied by overproduction of IL-12, IFN-γ and TNF-α. J. Immunol. 157, 798–805 (1996).

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

- 3.

Noris, M. & Remuzzi, G. Overview of complement activation and regulation. Semin. Nephrol. 33, 479–492 (2013).

CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

- 4.

Merle, N. S., Church, S. E., Fremeaux-Bacchi, V. & Roumenina, L. T. Complement system part I – molecular mechanisms of activation and regulation. Front. Immunol. 6, 262 (2015).

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

- 5.

Robbins, R. A., Russ, W. D., Rasmussen, J. K. & Clayton, M. M. Activation of the complement system in the adult respiratory distress syndrome 1–4. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 135, 651–658 (1987).

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

- 6.

Ohta, R. et al. Serum concentrations of complement anaphylatoxins and proinflammatory mediators in patients with 2009 H1N1 influenza. Microbiol. Immunol. 55, 191–198 (2011).

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

- 7.

Carvelli, J. et al. Association of COVID-19 inflammation with activation of the C5a–C5aR1 axis. Nature https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2600-6 (2020).

- 8.

Sinkovits, G. et al. Complement overactivation and consumption predicts in-hospital mortality in SARS-CoV-2 infection. Front. Immunol. 12, 663187 (2021).

CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

- 9.

Ramlall, V. et al. Immune complement and coagulation dysfunction in adverse outcomes of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nat. Med. 26, 1609–1615 (2020).

CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

- 10.

Rockx, B. et al. Early upregulation of acute respiratory distress syndrome-associated cytokines promotes lethal disease in an aged-mouse model of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection. J. Virol. 83, 7062–7074 (2009).

CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

- 11.

Mastaglio, S. et al. The first case of COVID-19 treated with the complement C3 inhibitor AMY-101. Clin. Immunol. 215, 108450 (2020).

CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

- 12.

Liszewski, M. K. et al. Intracellular complement activation sustains T cell homeostasis and mediates effector differentiation. Immunity 39, 1143–1157 (2013).

CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

- 13.

Yan, B. et al. SARS-CoV-2 drives JAK1/2-dependent local complement hyperactivation. Sci. Immunol. 6, eabg0833 (2021).

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

- 14.

West, E. E., Kolev, M. & Kemper, C. Complement and the regulation of T cell responses. Annu Rev. Immunol. 36, 309–338 (2018).

CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

- 15.

Break, T. J. et al. Aberrant type 1 immunity drives susceptibility to mucosal fungal infections. Science 371, eaay5731 (2021).

CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

- 16.

Cardone, J. et al. Complement regulator CD46 temporally regulates cytokine production by conventional and unconventional T cells. Nat. Immunol. 11, 862–871 (2010).

CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

- 17.

Yamshchikov, A., Desai, N., Blumberg, H., Ziegler, T. & Tangpricha, V. Vitamin D for treatment and prevention of infectious diseases: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Endocr. Pr. 15, 438–449 (2009).

Google Scholar